This is an excerpt from “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” by Jennie Alexander and Peter Follansbee.

There are several sources we use to learn about a 17th-century joiner’s tool kit. The surviving furniture retains many tool marks left by the joiners. These marks can include those from riving and hewing, layout marks for stock dimensioning and joinery, and even the types of plane blades used in surfacing the stock.

Probate inventories taken at the time of a person’s death often itemize details of their household belongings. Many examples of inventories include a tradesman’s tools listed in detail. For example: John Thorp of Plymouth died in 1633, and his estate included the following tools:

1 Great gouge, 1 square, one hatchet, One Square, 1 short 2 handsaw, A broade Axe, An holdfast, A handsaw, 3 broade chisels, 2 gowges & 2 narrow chisels, 3 Augers, Inch & 1/2, 1 great auger, inboring plaines, 1 Joynter plaine, 1 foreplaine, A smoothing plaine, 1 halferound plaine, An Addes, a felling Axe

William Carpenter, Senior, died in Plymouth in 1659. He had many tools listed in his estate:

Smale tooles att 10s; one axe and a peece of Iron att 7s; 4 Iron wedges att 8s; a foot and an old axe att 1s; …one old axe…; the Lave and turning tools att 13s; 3 Crosscutt sawes 15s; smale working tooles 12s; smale sawes 8s; an adds and 2 turning tooles att 6s; three Joynters 3 hand plaines one fore plain 10s; one bucse a long borrer one great goughe 10s; Rabbeting plaines and hollowing plaines and one plow att (pounds)1; 3 Drawing knives att 7s; 2 spokeshaves att 3s; Chisells a gouge and an hammer and a Round shave att 19s; 2 adds att 8s; one vise… 2 beetles…; a grindstone 15s; 2 axes att 6s #

The above inventories are found in C.H. Simmons, Plymouth Colony Records: Wills and Inventories. The values are expressed in pounds, shillings (s), and pence, (d). At this point in 17th-century New England, a joiner usually could expect about 2 shillings 6 pence for a day’s wages, a farm laborer about half that. A day’s work would be 12 hours in summer, and eight in winter.

Inventories can be enlightening and they can also be confounding. Some terminology is rather general. “Broad” and “narrow” are descriptive enough in some cases; yet in the same document the appraisers list the augers by size. The “inboring” planes Thorp had are moulding planes for decorating furniture and interior woodwork. William Carpenter’s planes were described better, hollows and rabbets among them, as well as the plow plane necessary for any panelled work. “Lave” is a phonetic spelling for a pronunciation of lathe.

Two detailed 17th-century English sources that are pivotal in the research concerning joiner’s tools are Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises; or the Doctrine of Handy-works Applied to the Arts of Smithing, Joinery, Carpentry, Turning, Bricklaying (1683) and Randle Holme’s Academie or Store house of Armory & Blazon (1688). Moxon’s book was published in serial form starting in 1678 in London, and it outlines the tools and techniques of several building trades. While these writings outline the tools used and some of the techniques, neither is strictly a “how-to” on the craft of joinery. It is important to remember that Moxon’s joinery section concerns itself with architectural joinery; making paneling, or “wainscot,” for rooms. He makes no mention of furniture at all. Holme’s work is more complicated. It is a guide for heraldic painters, detailing any images that can be found on coats of arms. However for our purposes it has a wealth of detail about all aspects of woodworking. Holme cites Moxon as one of his many sources, and both men probably also drew from Andre Felibien’s The Principles of Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, and Other Related Arts. (Paris 1676). Like Moxon, Felibien’s work is concerned with architectural woodwork, not furniture.

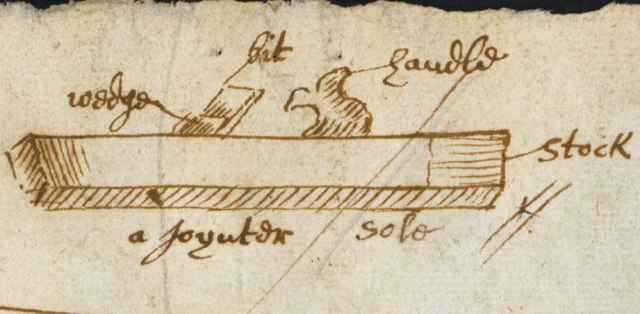

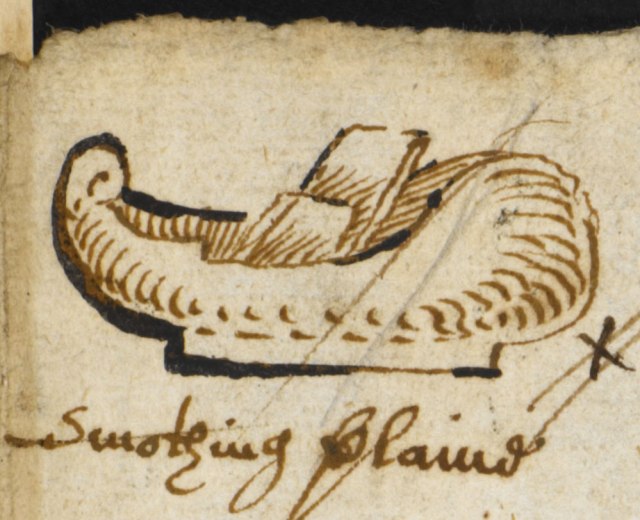

Both Moxon and Holme illustrate and discuss the necessary tools for joinery, some in more detail than others. Planes get extensive treatment; both works describe the parts of the plane, their function and the features that distinguish one from another.

Randle Holme described a fore plane. “…called the fore-Plain, and of some the former, or the course Plain; because it is used to take off the roughness of the Timber before it be worked with the Joynter or smooth Plain; and for that end the edge of the Iron or Bit, is not ground upon a straight as other Plains are, but rises with a Convex Arch in the middle of it; and it is set also more Ranker and further out of the mouth in the Sole of the Stock, than any other Bits or Irons are.” (Author’s italics.)

Both authors identify the jack plane as being the carpenters’ version of a fore plane. Yet the term “jack plane” does not appear in any probate inventory we have seen, it is always listed as a fore plane.

— MB