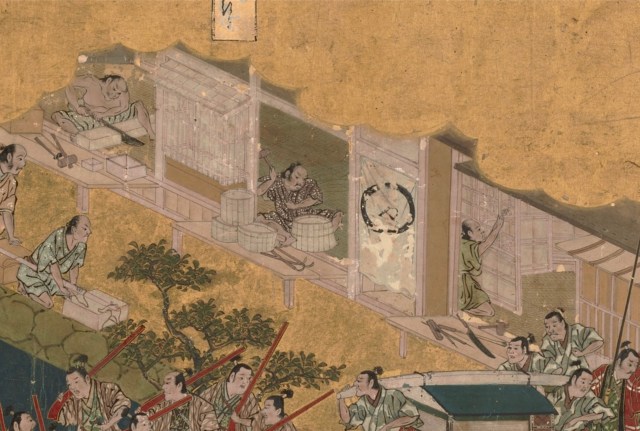

The craft groups and lumberyards in this second part of the Japanese woodworking festival cover a period of about 400 years. The occupations of craftspeople at work were painted on screens for castles and temples, carved on woodblocks that were bound into books, or sold as individual prints. The audience for the screens and books were the upper classes of society. Often, for the amusement of the readers, books featured “poetry contests” between craftspeople on opposing pages. These are similar to painted scenes of peasants going about their daily lives in seasonal calendars found in European medieval prayer books and manuscripts.

Some of the images are, like the one above, from works designated as national treasures or important cultural properties. In the last few years many have become available in higher resolutions and, especially the highly-detailed painted screens, are just plain fun to study.

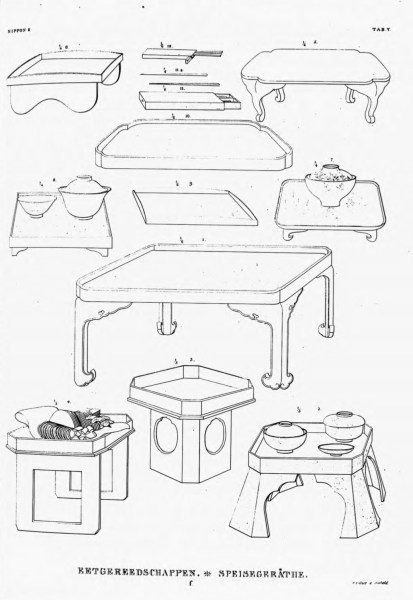

Similar to western societies, entire families were engaged in making goods for sale. Multiple generations commonly lived and worked in small two-room homes. The front room faced the street and was used to display and sell goods and as a workspace. The back room and small courtyard was the living space and also where much of the goods were made.

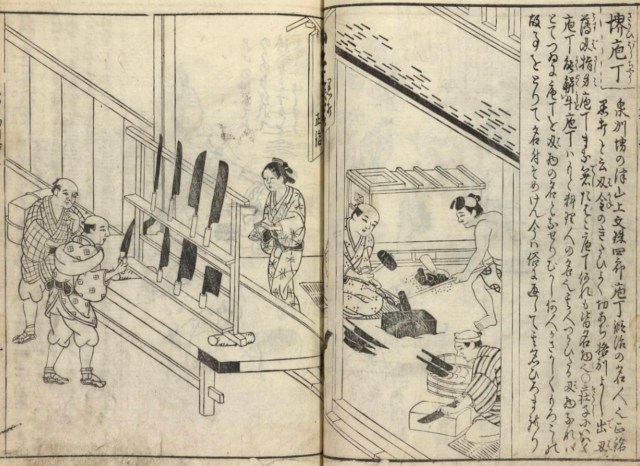

The Toolmakers

In his comments for this image Kaemmerer noted the blades and saws hanging at the shop front, small items in a box near the toolmaker and a display at the shop front that might be nails.

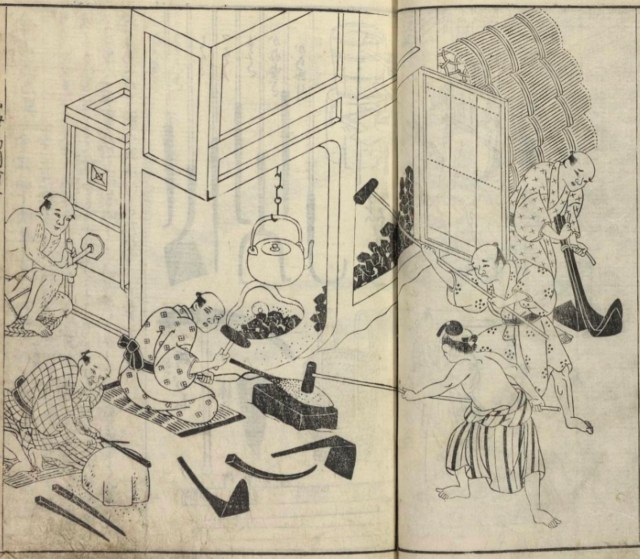

In this second image there is bit more detail and a with more detail and a better view of the forge used to heat the metal in a small shop. Below is a toolmaker with a much bigger operation.

In the same book by artist Hasegawa Mitsunobu a crew is crafting heavy tools for use in a quarry. A much larger forge is needed for this operation with a dedicated “forge man.”

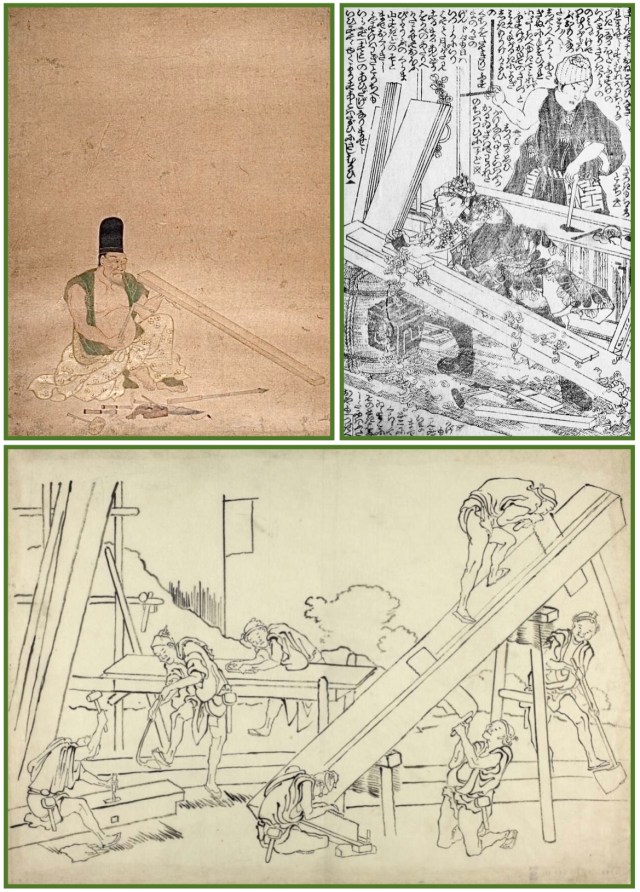

The Carpenters

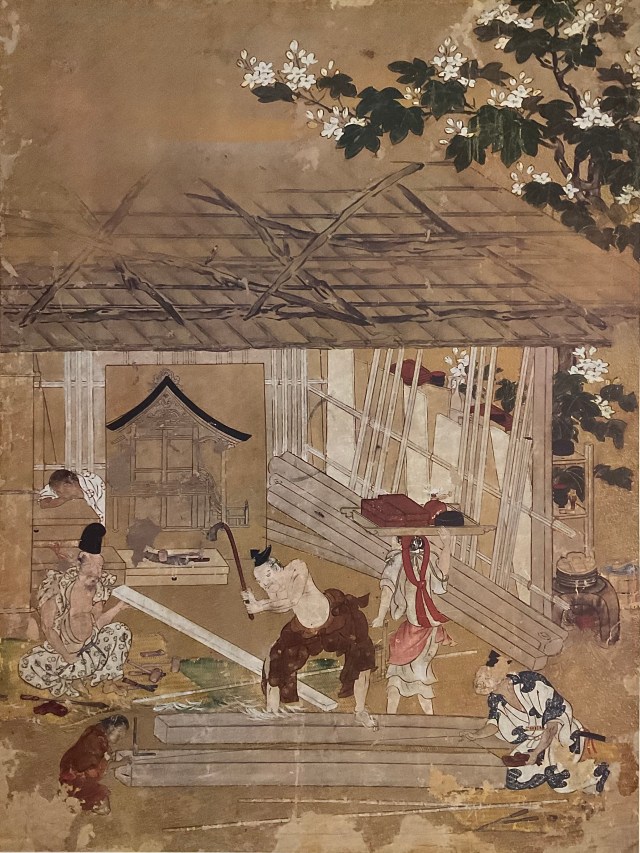

Several years ago I sent the top-left image (15th century) to Wilbur Pan. In his comments on his blog he noted there was no Japanese plane, but there was a yari-kanna, or spear plane, and this is possibly an indication of when the planes used today came into use. The image at top-right, with unknown artist and source, is notable for the tattoos on the carpenter in the foreground and nice curly wood shavings. It is just possible the plank acting as his workbench is a sake barrel.

The busy scene above (except for the guy in the back taking a nap) may be at the carpenter’s workshop with prep work underway or it may the building site. In the background is a drawing of the building plan, something not seen very often in these illustrations. One of the tools near the seated master is the yari-kanna, or spear plane. Other things to note are the tool box in front of the building plan and lunch has arrived.

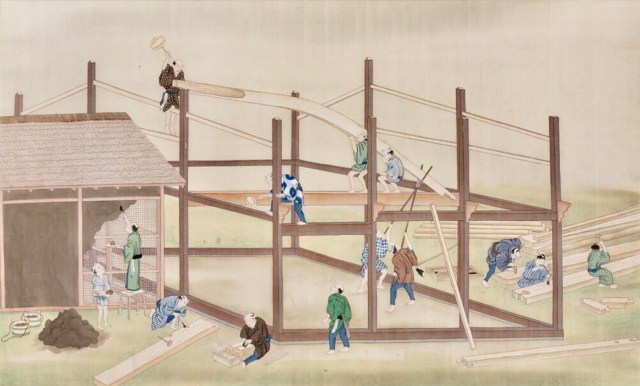

A very pristine building site of what may be, considering the size of beams, a warehouse. Seated at the corner of the building is the very important sharpener, because as we all know, sharp fixes everything.

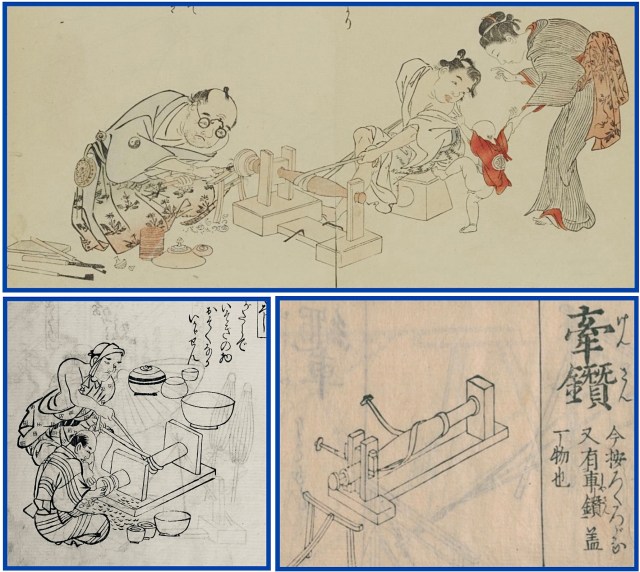

The Turners

The illustration at the top probably shows three generations of the turner’s family and emphasizes the family nature of the business. You can also see how stakes are used to stabilize the lather. The image of the lathe and stand is from the Kinmo-zu-i (Enlightening Illustrations), Japan’s first illustrated dictionary. The dictionary is comprised of 14 volumes of woodblock illustrations with written descriptions.

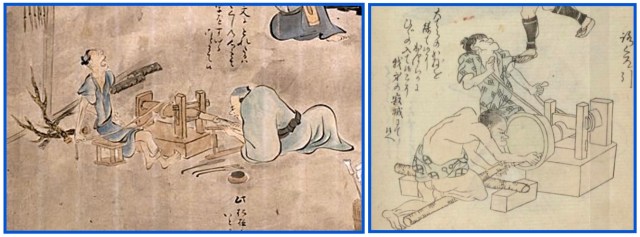

Working as the power for the turning lathe was an exhausting job as emphasized by these two images. On left, the worker stops and gasps for breath. On the right, his counterpart strains to keep the lathe turning. Also note the large brace employed to work on a larger container.

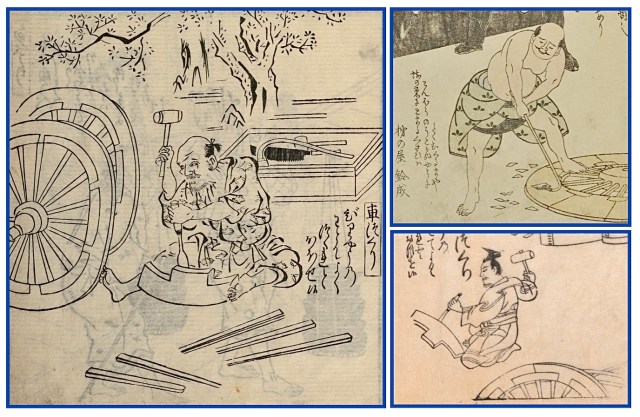

The Wheelwrights

Some things don’t change much over a period of 200 years: the tools are the same, the body is used as a work-holding device and the wheels are made the same way (except on the bottom-right – is that felly being held in place by magic?).

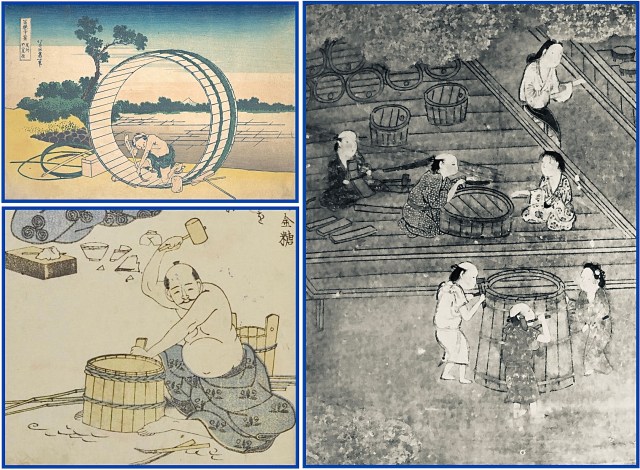

The Coopers

I’ve often wondered if Hokusai made that barrel extra large just to frame Mount Fuji.

Like the image from Eric Kaemmerer’s book, we get a good sense of how the family was involved in making goods for sale and how the living space was dominated by the workshop.

Back in 2016 (when we were all so much younger) I wrote a piece on Japanese and Estonian cooperage and included information and video of a Japanese company still engaged in making barrels. If you would like to read it you can find it here.

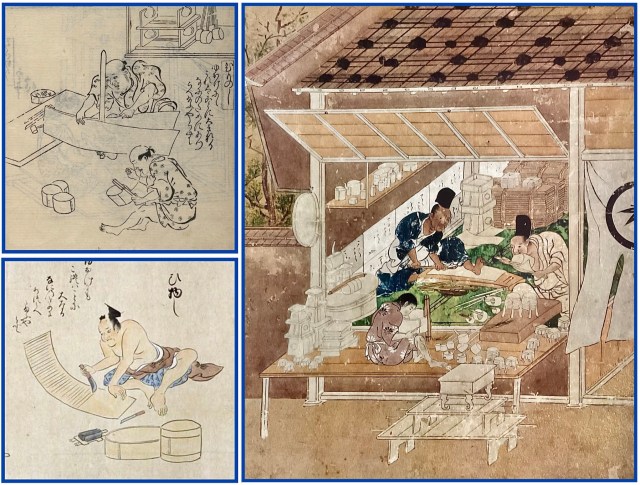

The Cypress Woodcrafters (himono-ya)

Working with hinoki, these craftsmen are making round containers, sanbo (a small stand for offerings in Shinto temples), trays, small tables and stands. After splitting thin sheets of wood, the wood is scored and bent into place. A clamp holds the piece together until it can be stitched together. In the large image the master uses a yari-kanna to smooth the wood and the worker on the right is bending (with the aid of his mouth) a sheet into a round shape. The worker in the foreground has a clamp in place as he stitches the wood together. Two sanbo are stacked to the right of the master and in the background supplies are stacked. The screen paintings from the Kita-in Temple are true treasures in depicting how artisans worked.

The Shamisen Maker

Many Lost Art Press readers make and play musical instruments, even banjos (hello, Mattias). So, I have included the shamisen in this post.

While the craftsmen on the right work on smoothing the neck of a shamisen, the guy on the left trudges home looking like the girls said “no way” or he got kicked out the band. The screens painted by Iwasa Matabei have so many interesting scenes and I couldn’t resist including him.

Although this is one of those staged photos taken in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it does give us a glimpse at how the shamisen is made. The drum is covered by an animal skin (formerly of an animal usually viewed as a pet) which the maker appears to be applying in this photo.

The woman on the left tunes the shamisen; the woman on the right plucks the three strings with a baci, a type of plectrum, cousin to the guitar pick.

The Comb Maker

Fans, umbrellas, sandals, small boxes and combs are just some of the many personal items that were, and continue to be, made of wood. I chose combs because they are a practical item used by women and men and are also an ornamental item.

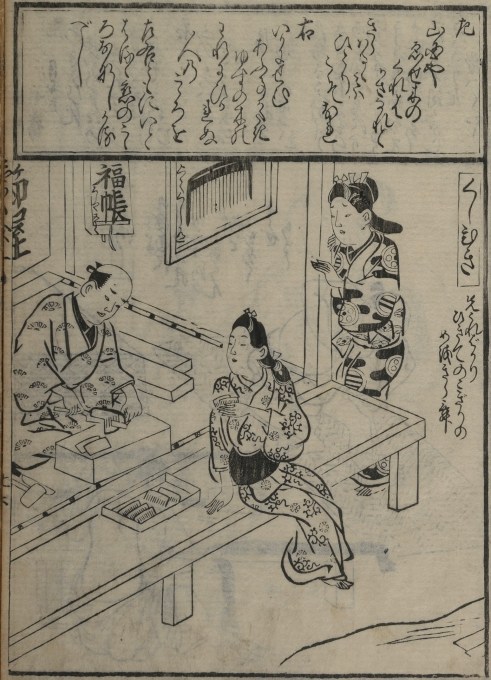

The kanban, or shop sign, makes it to easy find this comb maker. Comb making requires the skill to make precision cuts, both for blanks and to cut teeth that are evenly spaced. An ornamental comb, or kushi, required a high level of skill and refinement with finishing and decoration completed by a lacquer artist.

There are many painters in the books illustrating craftspeople at work, but I could not find one that was definitely a lacquer artist. However, we do have an illustration of Japanese sumac trees, urushinoki, being tapped for sap to make lacquer, or urushi.

Hara Yoyusai used the maki-e technique of sprinkling gold onto a lacquered surface before it hardened. This raises the design elements and provides texture. The comb on the bottom is gold and the fireflies are black. Note how the painted design extends over the teeth of the comb. The comb at the top has been repaired, a common practice, because there is still beauty in broken things.

The Boatwrights

Only one image of this craft and it calls for alteration: boatwrights building a big boat.

Bringing Lumber to Market and the Lumberyards

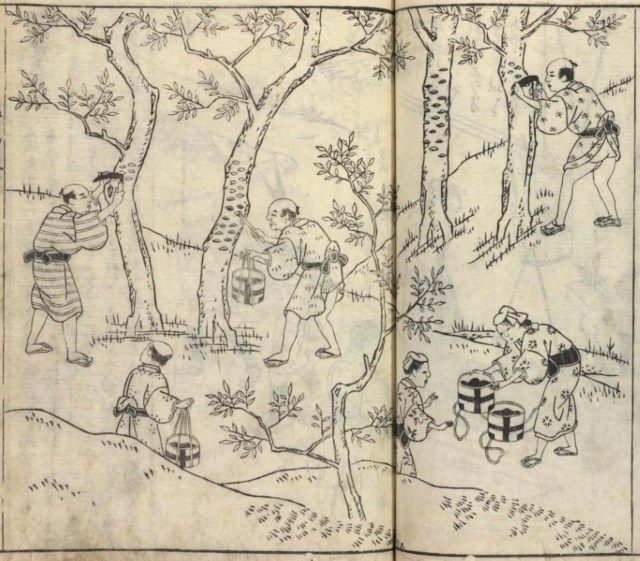

Trees are cut, trimmed and start the float down river to lumber merchants and their yards. These are scenes not usually found in the books featuring town-based craftsmen.

The three craftsmen at the very top of this post need only walk a short distance down their street and into the next panel of their screen to find a lumber merchant. The merchant probably received his supply via boat on the nearby river.

The 1657 Great Fire of Meireki was a conflagration that destroyed over 60% of Edo (Tokyo)and caused the deaths of over 100,000. After the fire lumbar yards were moved east of the Sumida river and further from the city. Thanks to the well-known 19th-century woodblock artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige we have two views of Tokyo’s Fukagawa-kiba lumberyard.

The lumberyard was its own city with a maze of canals, bridges and warehouses.

The lumberyards grew as more land was reclaimed.

In the early 1970s the lumberyards were moved further away to reclaimed land. The old lumber yard is now Kiba Park, the newer yards are Shin-kiba.

To bring the Japanese Woodworking Matsuri to an end I will leave you with a link to high-resolution images of the two screens of “Scenes in and Around Kyoto” (Funaki edition) painted around 1615 by Iwasa Matabei (Collection of Tokyo National Museum, National Treasure of Japan).

You can find the link here.

Each screen is made of six panels.

When you open the link click on the highest resolution. Scroll to the bottom of the page and you will see two links, one for each screen.

Your challenge is to find this pumpkin-panted Portuguese visitor:

–Suzanne Ellison