That’s a pretty good incentive don’t you think? Sharpen your tools and stop swearing.

Everybody Does It – A Sharpening World Tour

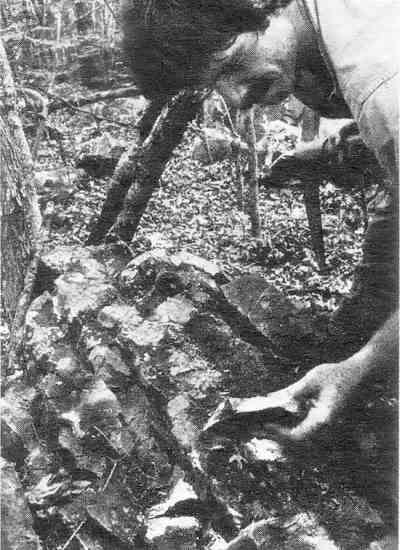

Neolithic polissoirs, characterized by straight grooves and a shallow basin, were used to sharpen axes, arrows and blades. If you encounter one you will see, and feel, that the grooves and basin remain smooth compared to the rough surface of the rest of the boulder. The Polisher in the photo above is on the Malborough Downs, Wiltshire, England. Polissoirs are also found in France.

Whakarewa is a grindstone used by generations of Maori. It sat in Mimiha stream until it was moved in the 1920s to make room for roads and other development.

The Romans mined whetstones in North Gaul (present day Northern France and Belgium), Crete and in other areas they conquered. The whetstones from North Gaul have been found in settlements dating to the 1st century C.E.

Some of the whetstones from North Gaul, such as the one above, have been found buried beneath the main support posts of buildings. It is not known what symbolic meaning the stones had for the builders or occupants of the buildings. Did a stone taken from the earth then used to sharpen tools or weapons become a powerful protector once placed back in the earth?

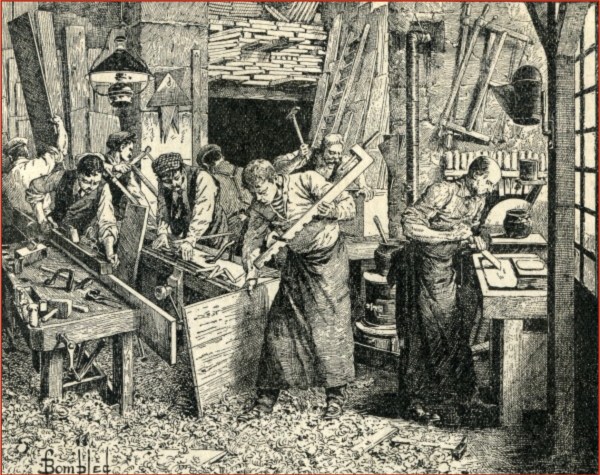

Roubo mentions sharpening stones as one of the necessary tools to be provided in a workshop. In Blombled’s crowded workshop, a sharpening station is right where it should be – close to the benches.

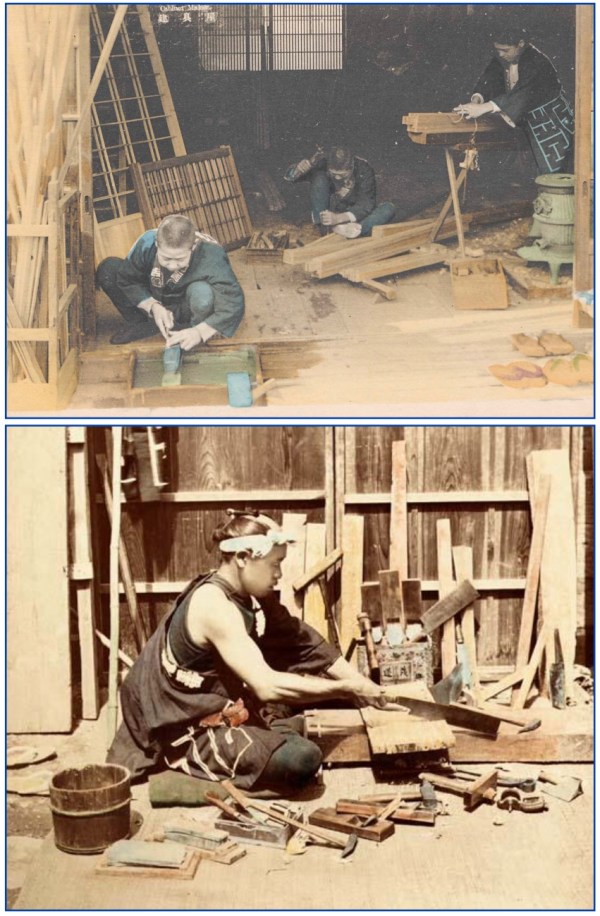

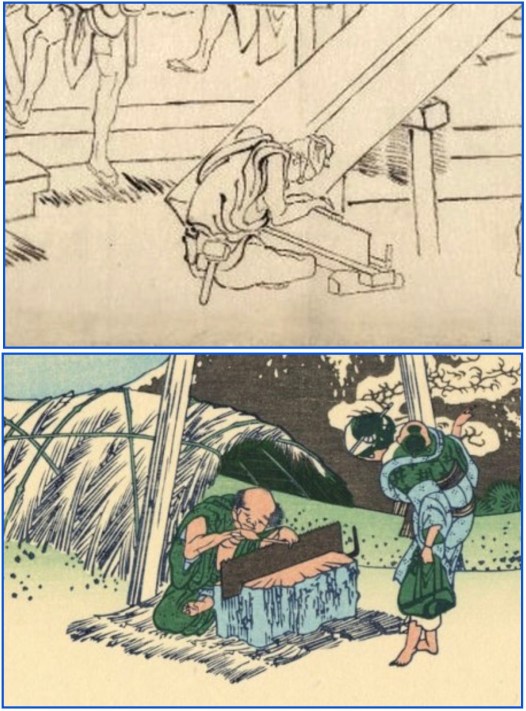

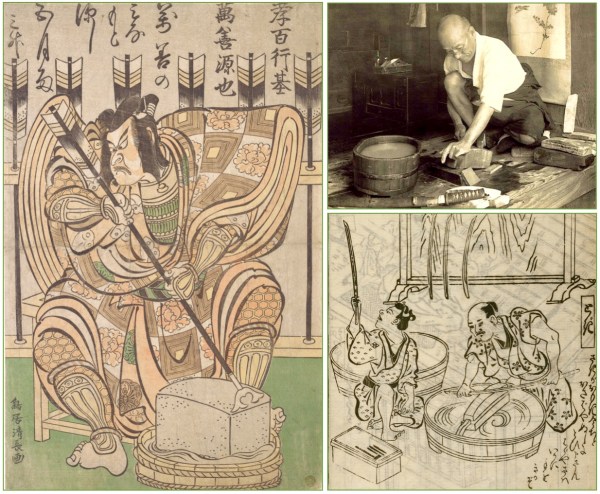

The Japanese workshops/work areas may be different from the European model, however, an area for sharpening was set up. At top, a chisel is being sharpened; in the bottom photo, (left foreground) sharpening stones and a water basin are at the ready.

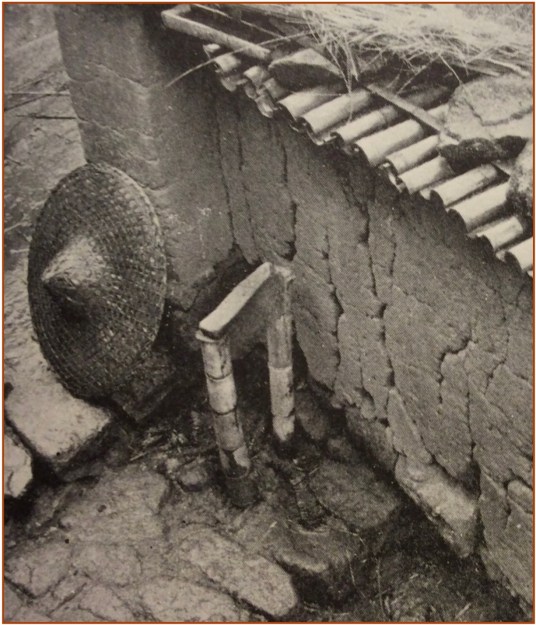

A sharpening stone was placed near an entrance. Whether you are coming or going, it’s a good reminder to sharpen your tools.

There is some evidence of pillars or other stone supports that were designated “sharpening spots” on large construction sites, especially when the constructions lasted decades or longer. The Cathedral of Valencia has such a spot near an entrance that is marked with deep vertical grooves.

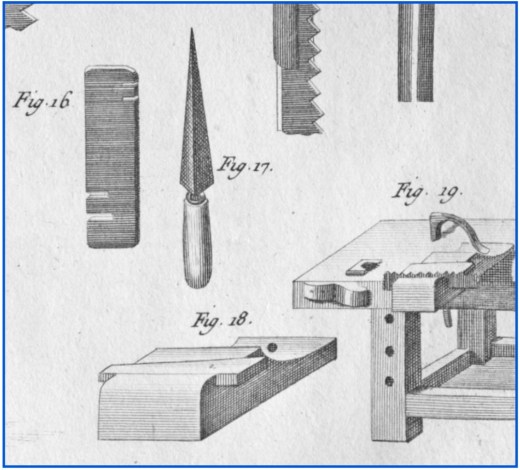

In Plate 12, Roubo illustrates the tools needed to sharpen saws. He includes a saw set, triangular file and a saw-holding vise to be secured on the workbench.

Positioned close to sawyers cutting massive pieces of lumber we find the saw sharpeners. One uses a vise made of blocks, while another has adapted a tree stump to serve as a vise. (The full-size images of the drawing and woodblock print are in the gallery at the end of this post.)

In this shop setting we see another saw vise option and it includes a stabilizing foot.

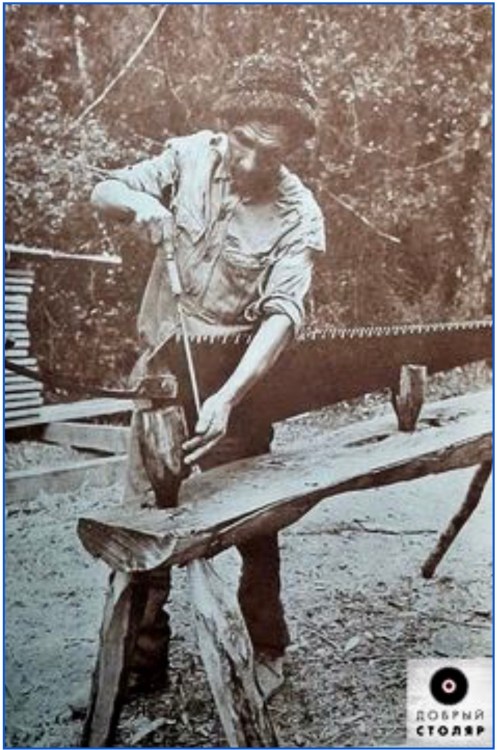

One more set-up for sharpening saws in the field (or forest). Using a low staked bench and shaped wooden “grippers” (and maybe some wedges) the pit saw is secured for sharpening. Side note: the photo is unattributed but is possibly Russian as the lower word in the logo (bottom right) is Russian for joiner or carpenter.

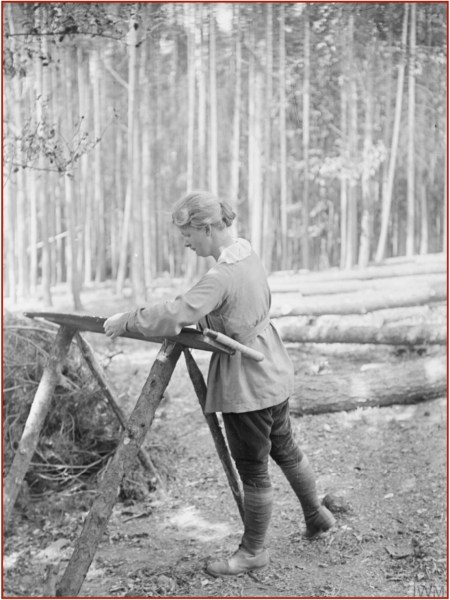

Is that a woman sharpening a two-woman saw in a lumber camp? Why yes, yes it is.

This composite is a reminder of how little has changed in using sharpening stones on metal edges. A domed stone in a water basin (or a nearby basin) is used by sword makers 200 or more years apart. In a kabuki play, Yanone (Arrowhead) Goro sharpens a double-headed arrow as he prepares to avenge his father’s murder.

Whetstones

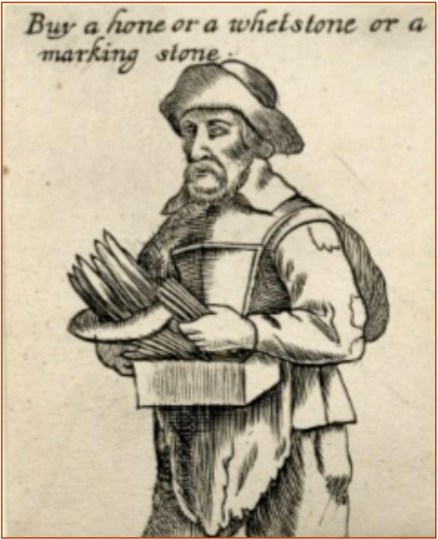

One of the great values of whetstones is their portability. Take them into the field or forest. Pack them in your tool box for the trip to the next job site. Whetstone quarries abound with some in operation for centuries.

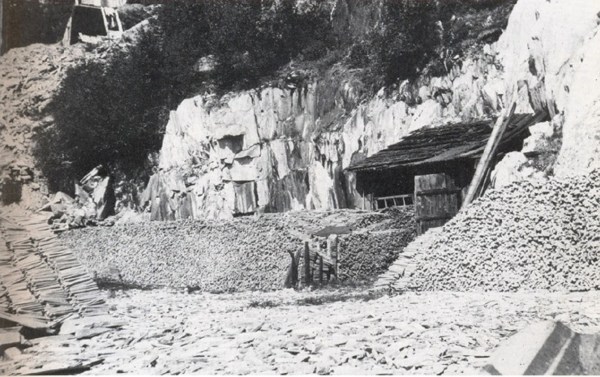

The Eidsborg quarry in Tokke, Telemark, Norway, was in operation from at least the 8th century until 1970.

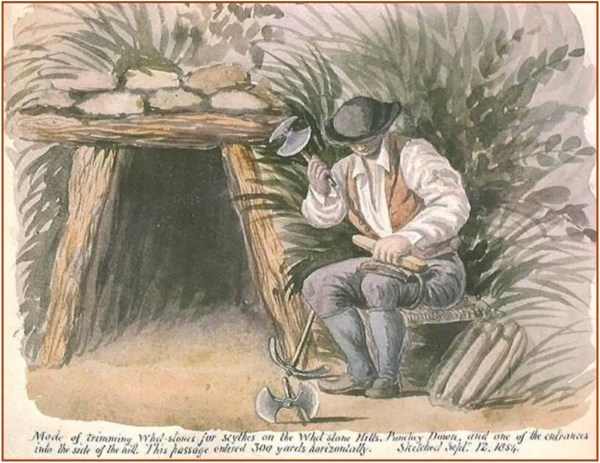

In the Blackdown Hills near the Somerset-Devon border in southwest England whetstones were mined from the 17th century to the early 20th century. Miners had small individual stakes on the side of a hill. The men of the family (father and older boys) dug the mine shaft, hewed out the stone and did the initial shaping with a basing axe. The wife and small children of the family did the final shaping. It was a hard way to make a living and exposure to fine stone particles and dust affected the health of the entire family.

Whetstone batts from the Blackdown Hills were used to sharpen scythes and other farm implements and tools.

One of the many explorations undertaken by Roy Underhill was to locate an old whetstone quarry near Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His trip, and what he found, is in a chapter of his book “The Woodwright’s Companion.”

Rotating Grindstones

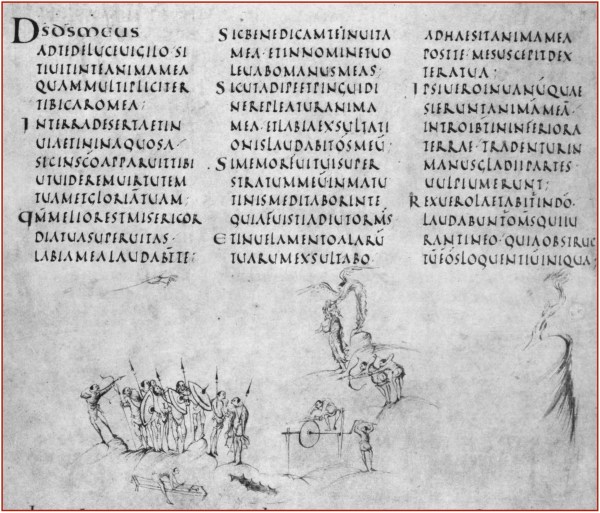

The earliest (so far) illustration of a rotary grindstone is from the 9th century “Utrecht Psalter.” It is supposedly a metaphor for “They sharpen their tongues like swords…” The grinder (grinding master?) sits high above the grindstone and to the side his minion turns a crank. Later manuscripts give us a better idea of the arrangement of this type of grindstone.

The top image provides a variation on a bird’s-eye view of this stationary grinder. The fresco below provides a much better view of how the grinder sat above the rotating stone. The lower half of the stone sits in a well of water and the minion turns the crank. This type of set-up could be found where large amounts of metal might be wrought, such as a large farming estate and shops making armor and weapons. The hand crank gave control over the speed of the grinding wheel.

If you lived in a city and had knives and scissors (or sciffars, or cifers) that needed sharpening a street vendor with a grinding wheel was readily available. The grinding wheel was propelled by a foot pedal and the vendor could use both hands. The vendor on the right has a cup (behind the larger wheel) to hold water or oil and on the frame there is a rag to wipe the blade clean (Chris has christened these rags, woobies).

The bicycle, both to turn the grindstone and to propel the cart, was another iteration of the portable grinder. Street vendors using foot or bicycle power can still be found in some large cities, but it is more common to visit a small shop or farmers’ market to have knives or scissors sharpened. That is why having a woodworker as a friend is a bonus.

Smaller versions of the stationary grinder became an asset to both large and small woodworking shops.

In 1810, Lewis Miller, carpenter and chronicler of York, Pennsylvania, has a small hand-cranked grinder in his shop.

And just over 100 years later hand-cranked grinders were still in use. Electric bench grinders are most often in use today and remain an important tool in a woodworker’s shop.

There is one more pre-electric “bench” grinder to examine and that requires a short trip to Switzerland in 1367.

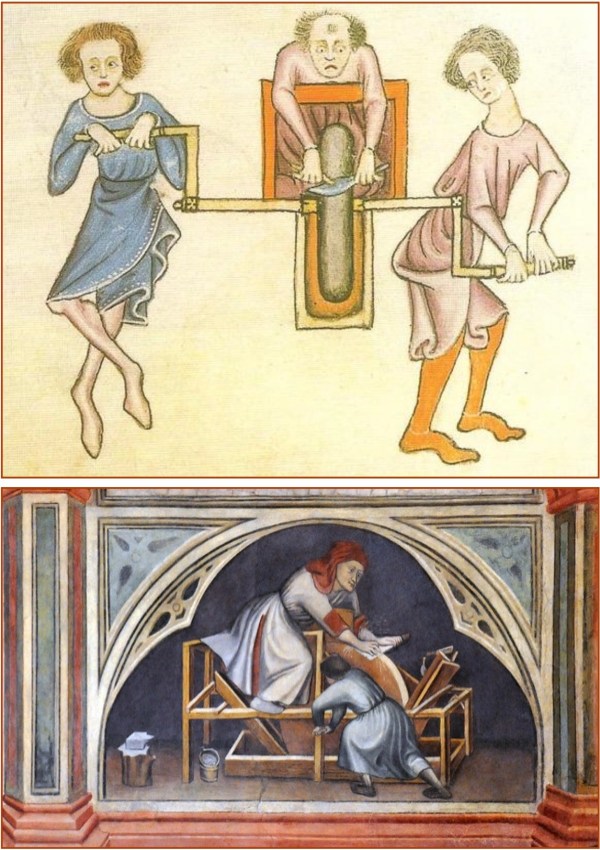

The “Spiezer Chronik” was commissioned to document the history of Bern, from its founding to the mid-15th century. It was written by Diebold Schilling, the Elder of Bern. The chronicle includes a lot of action from the very-long Burgundian Wars and wonderful color illustrations.

On page 367 there is a scene at a river. On one side stands an army and on the other a forest. The explanation of the scene is: “The Bishop of Basel wants to cut down the Bremgarten forest, for which the Berners provide him with the grindstone, 1367.”

The accommodating people of Bern provided benches with hand-cranked grindstones, water buckets and whetstones. Extra grindstones are arranged on the trees. The Bishop brought the axes. Sit astride a low bench and hand-crank the grindstone, what an idea.

Pick One

If you listen to most of the experienced woodworkers out there they will tell you it doesn’t matter what system of sharpening you use.

Use sharpening stones, water or oil. Don’t forget the woobie.

Use a file to get those burrs. And yes, bears do sharpen in the woods.

Go old school and use the classic “head-over-grindstone”method. If need be, your dog can be a counterweight.

The point is: chose a method, learn it and use it to sharpen your tools.

Resources

On this blog go to the Categories drop down menu (on the right) and look for “Sharpen This.” There you will find Chris Schwarz’s full series on sharpening.

Many books published by Lost Art Press include discussions on sharpening. One place to start is Chapter 10 “Essential Sharpening Kit” in “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest.”

You can read about the woobie, ahem, “The SuperWoobie” here.

— Suzanne Ellison