Who better to write a book about Jonathan Fisher, a late 18th century/early 19th century Maine woodworker and preacher, than Joshua Klein? Like Fisher, Joshua and his family are homesteaders in rural Maine, doing their best to live completely off the land. And Joshua is using in his own shop many of the same types of tools that Fisher had in his collection (not a surprise to those who know Joshua as the founder and editor in chief of Mortise & Tenon Magazine, a periodical that celebrates the preservation, research and recreation of historic furniture). As the crow flies, the Kleins live about 7 miles from Fisher’s Blue Hill farm.

Excerpted from “Hands Employed Aright: The Furniture Making of Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847),” by Joshua A. Klein.

In November 1810, Fisher began building a model of a “wood house.” Never one for technological stagnation, Fisher envisioned a building next to his house that was dedicated to producing lumber on a wind-powered sawmill that would also power his lathe. As a lumbering town, Blue Hill had numerous water-powered sawmills in Fisher’s days, but on his property at the top of the hill, Fisher had no access to a river or stream. What he did have, especially after years of clearing his property, was wind.

Although the memories of New England’s windmills are nearly faded, their abundance, especially along the coastline, is well documented. (2) As early as the 17th century, windmills (primarily for grinding grain) were being built in areas of New England without direct water access so they were not an unusual sight by the early 1800s.

As commonly known as they were, however, the construction of such a mechanism was beyond the skill of most craftsmen. One author has noted that the millwright’s job required a precision and care equal to the shipwright’s. The vision of a rural farmer building a windmill to saw his own lumber is quixotic. It seemed a project doomed to fail.

Reading through the journals during the two-and-a-half-years of construction of the mill is agonizing, especially as the recorded tally of his investment that included his own labor rises at $1 per day (the same rate as Joseph Murphy, a cabinetmaker of South Berwick (3) ) in the midst of numerous frustrated attempts at sawing.

We know the mill was generating power as early as April 1812, because Fisher recorded having his grindstone running “by wind.” After investing substantially and working on it for more than two years, Fisher recorded on April 19, 1813: “Worked upon saw gear and made an attempt to saw wood. Broke the [?]. Greatly disappointed in my hopes. Endeavored to resign to the will of God but found it a hard trial. I doubt not, however, but God intends good by this cross. Expense of wood house, etc. = $215.50.” The next day all that is recorded is: “Made a new experiment to carry my saw for sawing wood by wind – discouraged in it. Laid it aside = $216.50.”

Despite his discouragement, Fisher carried on and a few days later wrote, “first commenced sawing wood, with some, though small, good effect.” From here, only periodic sawing is recorded. The anticlimactic success of the sawmill is startling after so much labor and expense.

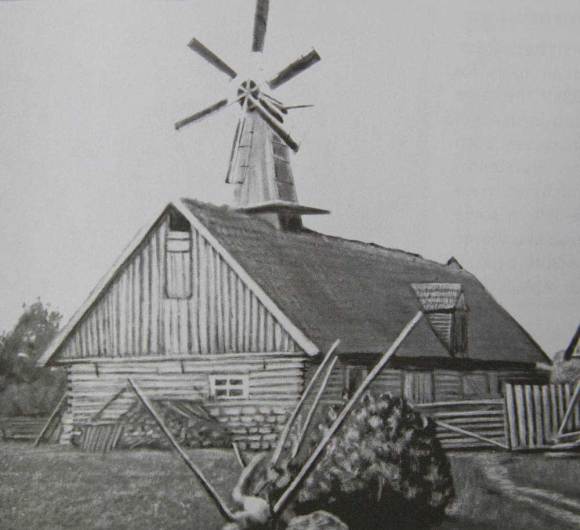

The wind power was also harnessed to drive the lathe. June of that year, Fisher documented: “Worked upon turning gear and set my lath a-going by wind.” Powering lathes with water power was common in production shops but wind-powered lathes were much less common. It’s hard to envision the practicality of such a setup. The irregularity of the wind must have been a challenge to deal with for the turning he was doing. The idea is not unprecedented, however. Windmill historian, Roy Gregory, has documented the use of an 8.5′-tall tower mill in a Lancashire, England, shop that powered a lathe and circular saw. The mill is described as having four 8′ long common sails with gears for regulating speed (4). Ants Viires, a historian of Estonian woodcraft, has photographed a small tower mill attached to the roof of a mid-20th-century spinning wheel workshop. It is likely that Fisher’s was similar in size.

The design of the wood house’s lathe is unknown. In Fisher’s room-by-room probate inventory taken in 1847, it listed a lathe and its chisels in the barn of which his son, Willard, was half-owner. Because two of the existing poppets do not fit the surviving lathe, it is assumed that Fisher had another lathe in the shop that was discarded when that building was taken down. Because no lathe (or any workbenches, for that matter) are listed in the probate inventory, it may be that these shop fixtures were built-ins. Often, probate inventories exclude these items because they were considered part of the shop building.

It is apparent that Fisher achieved his primary goal with this windmill project because he was able to generate lumber to some degree. But it must not have revolutionized his production enough because in June 1821, he disassembled the tower of his mill, never to speak of the mill in action again. Neither the 1824 Morning View painting nor the 1888 photograph of the wood house show any evidence to testify to the existence of the mill.

That Fisher referred to a least a portion of his wood house as his “shop” suggests that he eventually moved his tools out of the barn and into this dedicated space. The transition between workspaces must have been gradual because the installations of a new workbench and lathe are carried out over time amidst other woodworking projects. It is also conceivable that there always remained a small shop space in the barn for convenience sake.

In June 1823, Fisher was busy setting up his “shop chamber.” He moved his grindstone to a new location, built a “cupboard” for tool storage, constructed a portable workbench and installed a new stove. The reconfiguring of this workspace was likely due to his feeling “the infirmities of old age creeping stealthily upon him.” Perhaps this rearrangement facilitated his work.

2. Lombardo, Daniel, Windmills of New England: Their Genius, Madness, History & Future, On Cape Publications, 2003.

3. Burch, Abby, By His Account Rendered: The Business of Cabinetmaking in York County, Maine, 1815-1840, a modified master’s thesis, 2008.

4. Gregory, Roy, The Industrial Windmill in Britain, Phillimore & Co., 2005.