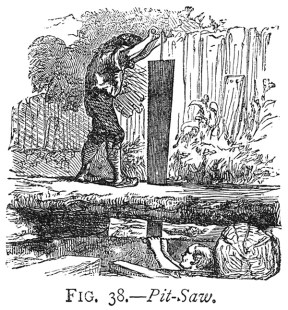

My father-in-law was by trade a sawyer, and a good workman; in fact, Thomas Leaf had the reputation of being the best veneer-sawyer in that part of the country. I, being destitute of employment, and no prospect of obtaining any, except by leaving England, which I was unwilling to do, Mr. Leaf undertook to teach me the art of mahogany and veneer sawing.

My father-in-law was by trade a sawyer, and a good workman; in fact, Thomas Leaf had the reputation of being the best veneer-sawyer in that part of the country. I, being destitute of employment, and no prospect of obtaining any, except by leaving England, which I was unwilling to do, Mr. Leaf undertook to teach me the art of mahogany and veneer sawing.

From the commencement of that business I gave promise of success, and it was not the least consoling to know, that at length I had found a trade wherein I could become respectable, and at least, something more than mediocre. It was soon my father’s boast, that with his “ big lad”—for I was too boy-like to pass for a man—with his lad “he could turn more veneers out of an inch plank than any other pair of craftsmen in the town.”

Thomas was an original in his way ; he had superior qualities as a workman, and seldom forgot to talk about them. He was generally upon good terms with himself; he had an unflinching independence of action, and a deep sense of honour and integrity regulated all his dealings. In a pecuniary point of view, my new trade was not so remunerative as it had been before the invention of the circular saw.

Our wages now averaged about two pounds each per week, and in some “good jobs,” amongst which the sawing of deep logs of Honduras wood into planks for coach panels may be particularized,—we sometimes earned as much as five pounds each per week; unfortunately we did not always use it wisely. Drinking was the curse of our trade, and nearly all who embarked in it spent one-half of their wages in that debasing practice.

It was often the boast of some of the sots, that the last Saturday night’s “shot” had taken the greater part of their week’s money. It is deeply to be lamented, that men will so lay waste their powers, and plunge themselves into misery—for it is a satire to call loss of health and substance, enjoyment. They were strangers to pleasure, and could not distinguish between enjoyment and sensuality. Often, when we refused to take a part in their reckless follies, they had recourse to the most dangerous expedients to force us, by damaging our tools, driving old files into the pieces we had to cut through, and similar destructive practices.

There is but little hope for the confirmed drunkard ; however bountifully he may be remunerated for his labour, he is never in a position to resist the encroachments that competition and individual grasping are always making upon him. The drunkard is rarely a thinking man. It was once a foolish opinion, that you never knew a good workman, but he was also a “ hard drinker.” That opinion is, fortunately for mankind, now exploded; and where is the virtue of the boast?

Can the drunkard think more deeply upon the intricacies of mechanics, science, and the arts, than the man whose head is clear of the fumes of intoxication? Are not his means thrown away upon a foolish, nay, pernicious indulgence? How often are his hopes of reward sacrifised to the avaricious dealer, who knows that half a man will, by necessity, be compelled to take half a loaf rather than starve; he knows the market value of an independence that will sell itself to an idol; such a one is ever on the downward road to famine and disease.

The meridian of veneer sawing was passed when I commenced the business; the mills were gradually superseding hand labour, and loud and deep were the curses our craft was daily venting against the new invention. They rejoiced at every accident that befel the machinery, and did not scruple, whenever an opportunity offered, to play off any diabolical scheme, that might injure or destroy their works.

I have known the ends of files industriously driven into valuable logs of mahogany; and I have heard with pain their rejoicings, when report has proclaimed the consequent destruction of the machinery. Has such wanton devastation been of any advantage to the perpetrators? Has it prevented the growth and the perfection of saw-mills? Are not they themselves now convinced of the superiority of machine over handsawn veneers, and that no cabinet-maker would now submit to work the latter?

Is the fact of hundreds being thrown out of employment by the introduction of machinery, a sufficient argument against its use? I would answer no! I believe that great, important as are its results already, that it is yet in its infancy, and that the most comprehensive mind can but dimly shadow forth its benevolent mission. I regard it as one of the great blessings of the Creator, who has destined the inanimate to conquer labour, by its iron bone and muscle— that man, the inventor and director, “infinite in faculties,” “in apprehension like a god!” shall some day work by his mental might.

Is machinery, then, to go on reducing labour, and our population to starve? No! Then how long is the present system of the labourers working, and the machinery reducing their rewards, to continue? Just so long as the artisans will allow it, but no longer! They are the machine makers—they are its workers; they may be its owners, and be themselves benefitted by its vast productive powers—and this they will be, as soon as they are determined to be MEN…

As the trade of veneer-sawing fell off in Hull by the multiplication of engine power, our occupation was confined to sawing the logs into boards. An opportunity now offered itself of transferring our business to the city of York. A merchant of that city, Mr. W , being over at Hull, and making extensive purchases of Messrs. Barkworth and Spalding, our employers, Mr. W. engaged us to go over and work for him, with an understanding that we were to be constantly employed on mahogany, and other rich woods. We reasonably expected, that where there was a demand for such a class of workmen, we should find remunerative employment ; so, in the late Autumn of 1822, we packed ourselves on board the Selby steam-packet, for York…

If, as a trade, the sawyers we had left behind us were generally a drunken class, they were not more circumspect at York. Here, any subterfuge that would give a pretext for “St. Monday’s” clubbing for drink, was eagerly sought after; and regulations, which in themselves appeared to be useful and necessary, were merely used as ready ways to indulgence. Hence, fines for a disregard of cleanliness at work, were in plenty.

To go to work on Monday morning with a dirty shirt on, or unshaven, called for the penalty of a shilling for each offence; to the forfeit, each man in the company was expected to contribute Sixpence—the whole to be spent in drink. This “ fuddling” once begun, it usually lasted two or three days. One of our “mates” made it a rule to begin the week with a dirty shirt on, and a black beard, whenever he wanted an extra indulgence; and in his case, the exception was the rule. The misery and desolation that haunted that man’s home may be well conceived: his wife haggard in countenance, lacking necessary food, half naked and desponding—his children, immoral and ragged…

In a few months, the hope we had cherished of constant employment here, at superior work, was blighted. The demand was not equal to the supply; the machine-cut work was at our heels, and was soon imported into our newly-adopted place, and we were consequently driven to seek work on coarser materials. This, to my father-in-law, was a source of continual annoyance, and he could not refrain from venting his disapprobation of our employers’ breach of promise. For my part, consideration has shewn cause for extenuation. There was not much skill required in our latter work, which, to me, was more grievous than the inconvenience of lower wages.

Christopher Thomson

The Autobiography of an Artisan – 1847

– Jeff Burks