Pride in Craft and Accomplishment

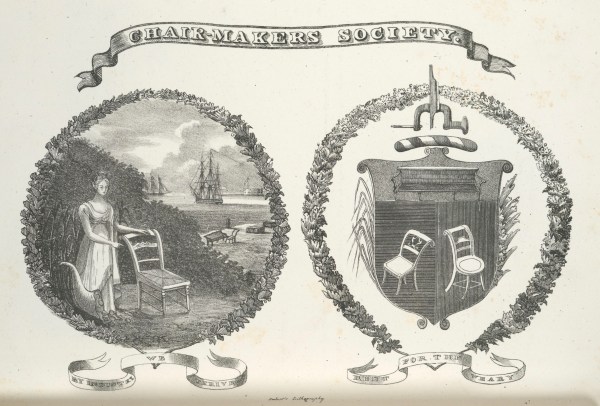

The completion of the Erie Canal, the first navigable water link between the Northeast and the Midwest, was cause for celebration. A grand procession was held with the participation of the various artisan societies, including 200 members of the Fancy and Windsor Chairmakers Society. We only have two examples of the banners they carried and both are loaded with messages.

In both banners there are examples of the furniture made by the Society’s craftsmen with the second banner including specific tools. “Rest for the Weary” is a clever way to advertise a chair, the product and also the benefit offered to the customer, a comfortable chair to sit in after a long workday. The illustration accompanying “By Industry We Thrive” is about commerce: the female figure and cornucopia symbolize peace and plenty, the chair at the front and the furniture in the middle ground are another reminder of the Society’s output, the ships in the background are the movement of goods between marker and market.

A third banner described in the Memoir had the motto “Support the Chair” with a double meaning. It was a compliment to the Governor of New York as well as an inducement to buy a chair. Regrettably, there is no illustration of eight boys carrying a large gilt eagle with a miniature chair in its beak.

By 1825, artisan or craftsmen associations and societies had been around for around about a half century. Participating in parades was a way to display pride in their craft, accomplishments and the contributions made by the skilled crafts in building the new Republic. It has to be noted the skilled women artisans and free black craftsmen were not invited to be part of the celebration. As for the unskilled workers that worked on the canal, they were nowhere to be seen.

Skilled craftsmen organized to protect the standards of the craft, settle disagreements between members, provide education, open libraries and provide mutual aid to members. Dues collected could be used to help injured or ill member and to support widows and children when a craftsmen died. Not all craftsmen chose to join these societies and were therefore not offered any of the protections of membership. Some societies were for masters and employers only. Journeymen, in turn, would form their own societies.

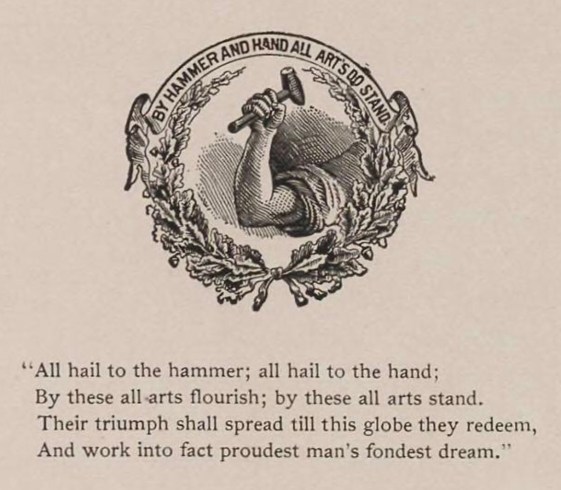

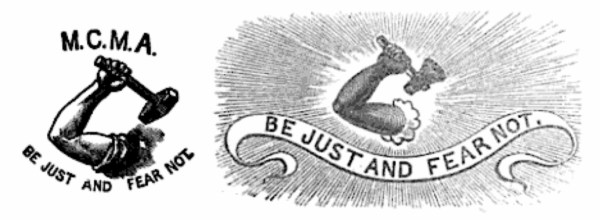

The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York was formed with 22 members from various crafts in 1785. They adapted the blacksmith’s hammer and hand as their emblem (and the blacksmiths borrowed the emblem from Hephaestus/Vulcan). The Carpenters’ Society of Baltimore was formed in 1791 and within a few years the carpenters would merge with other crafts to become the Baltimore Mechanical Society.

The Charleston Mechanic Society, with the motto “Industry Produceth Wealth,” formed in 1794 with an initial goal of preventing the hiring of skilled enslaved men over white craftsmen. A similar action was taken up by some Mechanic Societies in other Southern States.

In 1795 the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association was organized in Boston with Paul Revere as a founding member. One their initial aims was to do something about runaway apprentices.

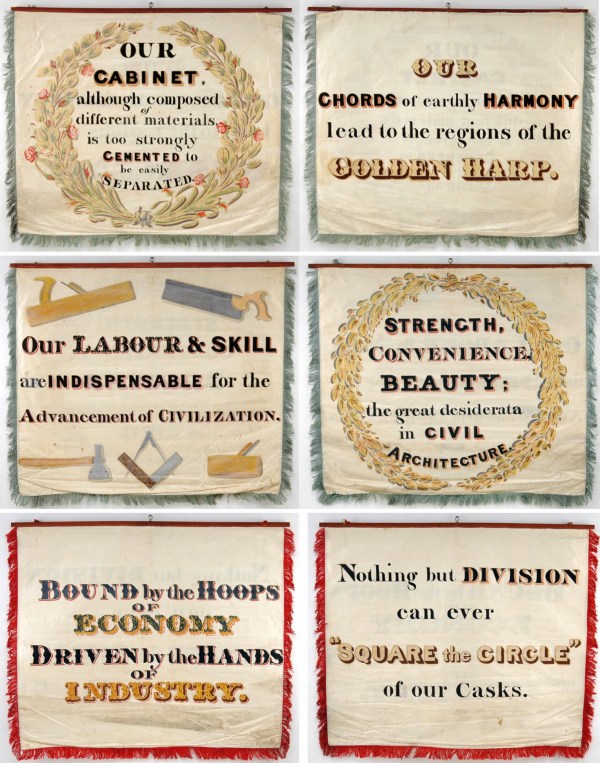

In 1815, 17 skilled craftsmen groups formed the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association in an attempt to “counterbalance the dominance of local society by merchants.” In 1841 the Association commissioned banners for a Triennial Festival. The festival was organized to promote municipal pride and the contributions made by the skilled craftsmen of the city.

To Be One’s Own Master

In an article for the Department of Labor’s history of labor relations, Edward Pesson wrote, “Skilled workers – variously known as craftsmen, artisans or mechanics – received from seventy-five to one hundred percent higher wages than the unskilled. Some artisans owned homes, modest dwellings to be sure, yet sufficient to contain work area, kitchen, living quarters for the family and in some cases for servants or apprentices.

“The tools they owned and their proficiency in using them gave skilled workers marketable assets which enhanced their sense of worth. Working independently or with others as journeymen in small shops directed by master craftsmen, they could realistically anticipate becoming masters someday.”

Well before the Erie Canal celebrations of 1825, the master-journeyman relationship had changed. Master craftsmen had comfortable earnings and business networks that allowed them to enter the emerging middle-class. Journeymen came to realize they would very likely never advance to be a master of their own shop.

By the early 1800s craftsmen’s societies that were originally confined to one craft, or to groups of skilled craftsmen, had changed to include tradesmen and merchants. For the master craftsmen this meant a transition from a working master artisan to a capitalist.

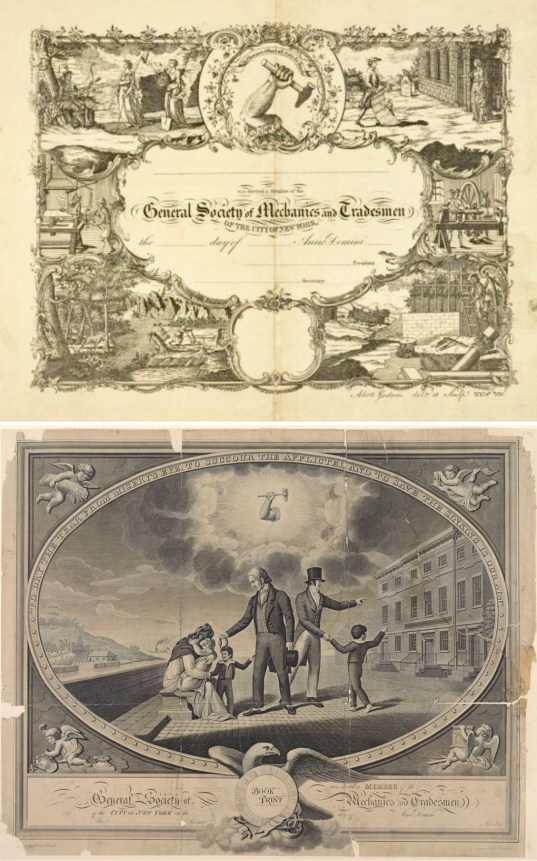

Originally, this certificate and book plate from the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York were destined for the gallery along with other Mechanic Society documents. After reading a few chapters from “American Artisans: Craft Social Identity 1750-1850” edited by Howard B. Rock, the documents are worth a closer look as the symbols used reflect changes in the mechanic societies.

In the membership certificate the hammer in hand emblem is prominent and in the corners are scenes of craft and mutual aid: craftsmen at work, symbols of peace and plenty (top, left) and aid brought to a grieving widow and child. By the time the book plate was issued in 1822 the Society became a sponsor of the Mechanic Bank and the symbols of craft diminished. Although the Society had established a school and library for apprentices the emphasis was more on commerce relationships. In the plate two tradesmen, not leather-apron craftsmen, offer charity to a widow and direct her son to the apprentice school. The small hammer in hand floating on a cloud is “an apt symbol for masters who had ceased to be sweat-of-the brow artisans.” The hammer in hand symbol was not trademarked and was used by other businesses such as the Vulcan Spice Mill in Brooklyn. The owner of the mill later used the emblem on boxes of Arm and Hammer baking soda.

Rest for the Weary

The flipside of the chairmakers’ motto is the sheer number of work hours and stagnant pay of a journeyman. Work hours were sunrise to sunset, six days a week. In the summer this could mean working 14 to 16 hours with short breaks for breakfast and lunch.

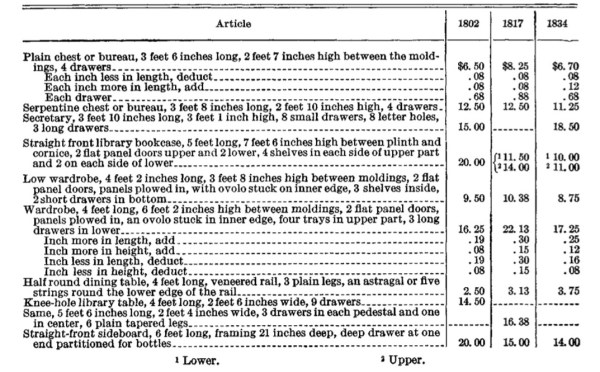

Three New York City cabinetmaker price books illustrate the stagnation of wages. The first price book was issued in 1802. The next revision was not until 1817 and the third revision was in 1832. In the “History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928” by the Department of Labor. A portion of a price comparison table is below (pounds and shillings used in 1802 and 1817 were converted to dollars).

The 1802 book states “men working by the day are to be paid in proportion to their earnings by the piece, and find their own candles.”

Even with skilled craftsmen earning much higher wages than unskilled workers, living conditions of skilled craftsmen were crowded and lacked adequate sanitation. This was not unique to large cities like New York. Similar conditions were common in mid-size cities and towns in the South and Midwest. The workers that made up most of the urban populations owned 5 percent or less of urban wealth.

Entering a skilled craft and training for years with the promise of advancement, good wages to support a family and ultimately having enough to support oneself in old age was the expectation of a journeyman. In April 1809 the Carpenters’ Strike Manifesto was published in the American Citizen newspaper and addressed to the public. The Manifesto was from the Journeymen House-Carpenters and involved a strike to work for no less than 11 shillings per day. This statement explains the frustrations of the journeymen:

“Among the unalienable rights of man are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. By the social compact every class of society ought to be entitled to benefit in proportion to its usefulness, and the time and expense necessary to its qualification. Among the duties which individuals owe to society are single men to marry and married men to educate their children. Among the duties which society owes to individuals is to grant them compensation for services sufficient not only for the current expenses of livelihood, but to the formation of a fund for the support of that time of life when nature requires a cessation from labor.”

The Manifesto continues with an account of annual income and expenses. Using a base of 300 work days (Sundays and several days for possible illness or injury were deducted), earning 11 shillings per in day in the spring through autumn and 10 shillings through the winter, total annual earnings would be $400. After deducting expenses for house rent, firewood, food for the family, work clothes, replacement of worn or lost work tools and a small amount for contingent expenses the journeyman would have $42.50 left for the wife’s and children’s clothing, education of the children and family illnesses.

The Manifesto ends with “And now let us ask those that are fathers of families to judge what will be the amount of the surplus for the maintenance of old age?”

Readers from Philly may be asking why your city’s craft societies have not be mentioned. Fear not! In the next post your fine city will figure prominently in the struggle to improve the wages and work hours of journeymen.

The gallery has a few more mechanic society membership certificates and banners.

— Suzanne Ellison