This is an excerpt from “Ingenious Mechanicks” by Christopher Schwarz.

Sometimes I wonder why I research old workbenches, build them and write about them. I know my critics and friends wonder the same thing.

The truth is, I have a gland – well, it feels like a gland – deep inside my torso. It’s located a bit above my tailbone and in front of the base of my spine. Ever since I was a boy, that area would tingle and throb when I ventured into places I wasn’t allowed.

(My critics would say the location of that gland – or whatever it is – is also where a lot of crap is produced in the human body.)

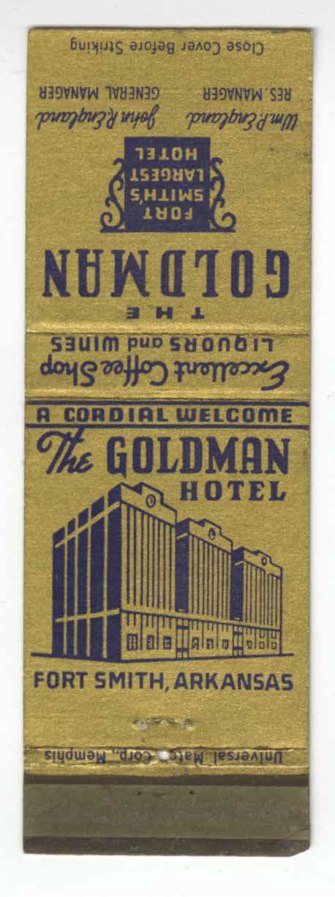

I was 6 or 7 the first time I felt it. My family attended First Presbyterian Church in Fort Smith, Ark., which is downtown and surrounded by empty buildings from the town’s 19th-century heyday. Next to the church was the derelict Goldman Hotel, a landmark six-story building built in 1910 that was the center of the town’s social scene until World War II.

The building was shut to the public at about the time my family moved to Fort Smith in 1973 (and demolished in the 1990s). But I spent every Sunday and Wednesday in its shadow and soon began sneaking out of Sunday school to explore the hotel through an opening on the building’s west side.

Though the Goldman was dilapidated – it had been an apartment building in its last days – there were remnants of its glory and its rich ornamentation throughout. Furniture. Light fixtures. Tiles. Mouldings.

That was the first time I ever felt that odd tingle. It was better than any high I have achieved with alcohol (or the banana peels I smoked in college). And I have chased after that feeling my entire life.

I have a thing for old and abandoned places. I love to explore overgrown concrete battlements that line harbors and rivers. Abandoned houses – we had a creepy overgrown one on our farm – are like a sip of bourbon. Multi-level factories filled with garbage, graffiti and old equipment are like a multi-day bender.

I knew I was wrong in the head (or the gland) in 2012 when I became halfcrazed about buying an old brewery in Covington, Ky. It had two flooded subbasements and a network of unexplored lagering tunnels that staggered off below the old city.

During a tour of that building, I encountered a deep pit in its basement. I threw a rock down the hole and didn’t hear it splash or hit bottom.

“Where does it go?” I asked the real estate agent.

Her reply: “We have no idea.”

I thought: “I have a flashlight and rope in my truck.” Behind me, I heard my wife, Lucy, call out: “Nope! We are done here!”

It probably was the right decision.

At other times, the gland acts up when I’m not in physical danger, but when I’m on the precipice of obsession. One week I flew to New York City and visited Joel Moskowitz of Tools for Working Wood. The highlight of that trip was paging through his 20th-century reprint of A.J. Roubo’s “l’Art du menuisier.” Like most woodworkers, I had seen the workbench illustrated in Plate 11 of Roubo’s multi-volume book many times before. But I hadn’t seen Roubo’s whole work – nearly 400 pages of plates. And many of the plates showed this simple bench in use for all manner of operations, from installing moulding in an apartment to sandshading veneer for marquetry.

While sitting on Joel’s couch with this giant tome on my lap, I became as intoxicated as the day I first ducked into a broken window at the Goldman Hotel. The feeling was so powerful that it verged on physical pain.

When I returned to Cincinnati, I felt physically compelled to build that workbench. I ripped up the editorial calendar for the 2005 issue of Woodworking Magazine and presented a new plan to the magazine’s staff to satisfy my personal lust: Build the 18th-century Roubo workbench using yellow pine (to make it less expensive).

I offered to do all the work – building, writing and illustrating – so no one objected. Or perhaps they were wary of crossing me because I looked a bit crazed. I had drafted my plan the night before and hadn’t slept much.

Building that first Roubo workbench and putting it to work was like mainlining the unknown for me – like exploring a forgotten Soviet missile silo or finding a passage to catacombs beneath my house.

Building that Roubo bench led to making the Holtzapffel workbench – a German/English hybrid. Then a Nicholson bench – the classic English workbench – and about a dozen variants of benches from Europe, the U.K. and North America.

It has been a 13-year obsession with no end in sight.

— MB