In 1744 John Wister built a summer house in Germantown, a rural area northwest of Philadelphia. The house later became the primary residence of the family and was known for its gardens, orchards and farm. When Charles Jones Wister (1782-1865), grandson of John, inherited the property he named it Grumblethorpe. He took the name from ‘Think-I-To-Myself’ a comedy by Edward Nares.

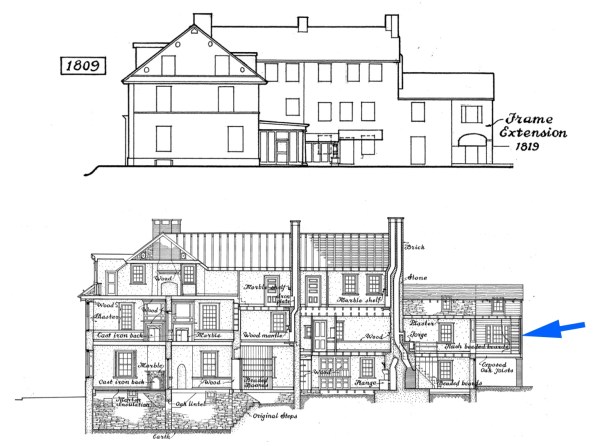

The Historic American Building Survey of 1934 notes, “Charles J. Wister had a taste for mechanics and in 1819, added a frame workshop.”

Wister’s workshop was on the second floor of the extension with a loft above. In the photo of the shop you can see the steps in the back left corner leading to the loft.

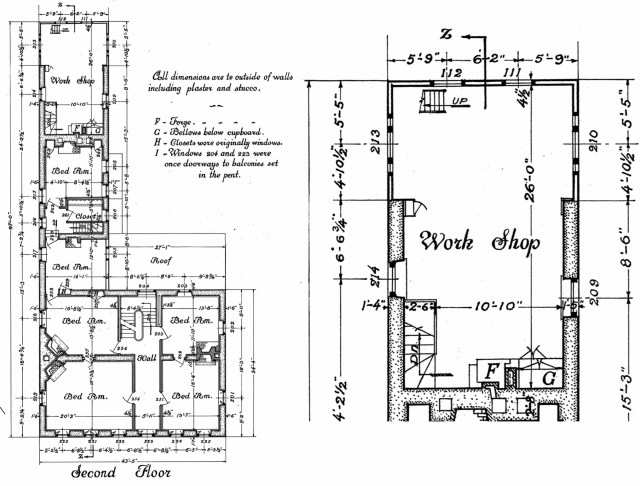

In the survey drawing of the second floor the workshop addition is at the very top, on the right is an enlargement of the shop. His shop was a generous 26’ by 10’-10’’ with a forge (F) connected to the chimney and a bellows (G) that was positioned below a cupboard.

The lathes (see photo) are under the windows in the back right corner. The cabinetmaker’s bench was likely on the left hand wall (under window #213?).

In 1920, a year before the workshop photo was taken, Jones Wister, great-nephew of Charles, published ‘Jones Wister’s Reminiscences’ with a chapter on his great-uncle. Here are excerpts with a brief description of the workshop:

”…The youngest of his family, born 1782, he early showed desire for learning and excelled at school and in college. He was celebrated as an astronomer, poet, lecturer and skilled mechanic.

Much time was given to his books and philosophical studies. His recreation was found in his workshop, where he had a forge, two turning lathes, and a cabinet-maker’s workbench, together with numerous mechanical tools.

At the last visit I paid my cousin at Grumblethorpe, I asked permission to revisit his father’s workshop, and found it just as I remembered and my great-uncle had left it, everything covered with dust, but intact, as it was sixty or seventh years ago. Nothing had been disturbed. He was to Germantown what the Weather Bureau is to the country. Three times daily he took the temperature, read his barometer, making careful notes, which were regularly published in the Germantown Telegraph, then owned and edited by Philip R. Freas.

He had an observatory, equipped with a telescope, through which he watched the heavens, and upon every clear day, observed the sun crossing the zenith. He issued bulletins of the time, and every clock in Germantown was set by his standard.

…He was a remarkedly versatile genius, for besides all his other accomplishments, he could repair clocks, and many which needed repairs were put into working order by his hands…

I should have taken more interest in my great-uncle’s educational researches, had not his shop possessed greater attractions. The long and short foot lathe, beautiful cabinet-maker’s bench, not to mention the blacksmith’s forge, won my enchanted admiration, and were much more to my taste. For here it was he turned the Wister tops, celebrated among all Germantown boys. These tops were made from dogwood, could not be split, but could split the tops of any playmate opponent, whose top was unlucky enough to be hit.

There are a few men still living today for whom my great-uncle turned a spinning top…He was a merry and humorous old gentleman, and when a new boy would be presented to him would astonish him by asking, “Why is a cranberry tart like a pump handle?” After the boy had puzzled awhile, he would quietly say, “There is no resemblance.”

The Bucks County Historical Society in Doylestown, Pennsylvaia has some of the tops make by Wister, other small items and some of his tools.

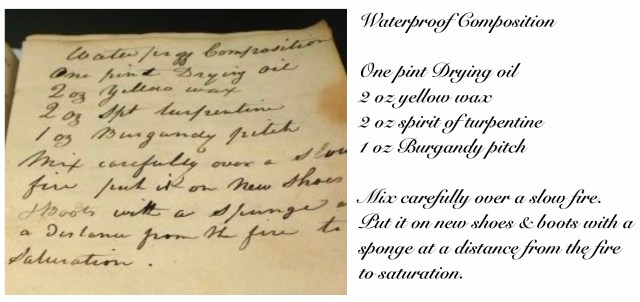

In 1820 Wister started a notebook to record his workshop activites and titled it, ‘Various Recipes & Formulae Used in the Shop.’ I believe the notebook is in the Eastwick Collection of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia with no digital copy available. However, in early 2010 an enterprising young intern at the APS posted several photos of items from the Eastwick Collection including this recipe from one of Wister’s notebooks:

Charles Wister was one of the early users of photography in Philadelphia and, according to notations in the APS archive, he took photos of Grumblethorpe. Did he take photos of his workshop? If so, and if they survived, the APS may have them.

Charles Wister was one of the early users of photography in Philadelphia and, according to notations in the APS archive, he took photos of Grumblethorpe. Did he take photos of his workshop? If so, and if they survived, the APS may have them.

What mysteries are waiting in the the various archives holding Charles Jones Wister Sr.’s notebooks and photographs? For now, we have one photograph taken 56 years after Wister died and a sparse account of the workshop that is dated around the same time. I will be sending a note to the Operations Manager for Grumblethorpe to find out what remains in the workshop and possibly get some photos.

—Suzanne Ellison